Opening: September 26, 2019

Deadline: November 25, 2019

Conditions: under 30 years old

Entry fee: Free

Prizes: £1,000, valuable prizes, participation in exhibitions and conferences in Japan, Spain, USA and UK

The 2019 IAFOR Documentary Photography Award is now inviting submissions on the theme, “Reclaiming the Future”.

The IAFOR Documentary Photography Award was launched by The International Academic Forum (IAFOR) in 2015 as an international photography award that seeks to promote and assist in the professional development of emerging documentary photographers and photojournalists.

As an organisation, IAFOR’s mission is to promote international exchange, facilitate intercultural awareness, encourage interdisciplinary discussion, and generate and share new knowledge.

The award has already been widely recognised by those in the industry and has been supported by World Press Photo, British Journal of Photography, Metro Imaging, MediaStorm, Think Tank Photo, University of the Arts London, RMIT University, The Centre for Documentary Practice, and the Medill School of Journalism.

Each applicant may submit 10 to 20 images related to the award theme, either in the form of a photo-essay or as a collection of single images.

Applicants must be 30 years old or younger on November 25, 2019 OR enrolled in part-time or full-time education on November 25, 2019 (proof may be required).

The majority of images should have been made during 2018-2019. However, at the discretion of the judges, images made earlier than 2018 will be allowed if they form part of a photo-essay continued during 2018-2019.

Prizes

Grand Prize

- Cash prize of £1,000 GBP from The International Academic Forum (IAFOR)

- A grant of up to $500 USD towards airfare and accommodation, and a scholarship to cover full conference registration fees for the IAFOR conference at which their work will be showcased*

- Acceptance into the Metro Imaging Mentorship Programme together with £1,000 GBP credit to spend on Metro Imaging services such as scanning, printing and mounting

- Included in World Press Photo’s final list of nominees for the Joop Swart Masterclass

- Tuition fee waiver for a MediaStorm Multimedia One-Day Workshop and free access to MediaStorm’s Online Training Videos

- Think Tank Photo Airport Advantage roller bag

Second Place

- Tuition fee waiver for a MediaStorm Multimedia One-Day Workshop and free access to MediaStorm’s Online Training Videos

- Think Tank Photo StreetWalker v2.0 backpack

Third Place

- Tuition fee waiver for a MediaStorm Multimedia One-Day Workshop and free access to MediaStorm’s Online Training Videos

- Think Tank Photo Exposure 13 shoulder bag

Honourable Mentions

- Free access to MediaStorm’s Online Training Videos

- Think Tank Photo Multi-Mount Holster 20 camera bag

Photography to be exhibited at IAFOR conferences in Japan, Hong Kong, Spain, USA and UK.

Invitation to an IAFOR conference.

Website: https://iaforphotoaward.org/

IAFOR Documentary Photography Award 2018 Winners

Grand Prize

© Ezra Acayan, The Philippines

More than 27,000 dead: This is the result of a two-year war on drugs in the Philippines.

In 2016, Rodrigo Duterte became the President of the Southeast Asian republic. His campaign promised him to win the election: He threatened those connected to drug consumption and sales with the death penalty, called for vigilante justice and allowed the police to act with brutality under complete impunity.

As President, Duterte has likened himself to Hitler and vowed to massacre millions of drug users. Dealers and users were murdered, as well as countless innocents and children – mostly the poor.

An estimated 30 people are killed each day across the country. The United Nations appealed in vain to the Philippine government to investigate extrajudicial killings and to prosecute the perpetrators, while the International Criminal Court has begun preliminary examinations into these alleged crimes against humanity. The war continues however.

This photo reportage hopes to illuminate both the violent acts carried out in the Philippines as well as the questionable methods of Duterte and the police. With thousands dead in two years and with four years left in Duterte’s term, it has become more crucial than ever to record these atrocities.

Second Place

© Subhrajit Sen, India

Sanjay Gope has never missed a step, this is because he has never taken one. The 18-year-old has been in a wheelchair all his life.

Sanjay Gope comes from Bango, a village six kilometres from the Uranium Corporation of India Limited’s (UCIL) mine in Jaduguda town, in Purbi (East) Singhbhum district of Jharkhand, the poorest state of India. UCIL, a government of India entity, dug its first mine there in 1967. The ore processed in Jaduguda and six other nearby mines is converted into yellowcake (a mixture of uranium oxides) and sent to the Nuclear Fuel Complex in Hyderabad.

Sanjay’s father is a daily wage labourer, his mother works in the paddy fields – as do most of the people in these villages. A few work in the UCIL mines, others say they were promised jobs that failed to come their way. When Sanjay was two, his parents took him to the UCIL hospital because he did not walk. The doctors assured Sanjay’s parents that they did not need to worry. So they waited patiently, but their son never took his first step – or any steps.

Sanjay is among many children in Bango – a village of around 800 people (most from the Santal, Munda, Oraon, Ho, Bhumij and Kharia tribes) – who were born with congenital deformities or died because of them. According to a 2007 study by the group Indian Doctors for Peace and Development, the rate of children dying from such defects was 5.86 times higher in villages close to the mine (0-2.5 kilometres) than those in settlements 30-35 kilometres away. Women in these villages have reported a high number of miscarriages. Diseases like cancer and tuberculosis have killed many who worked in the mines or lived near the processing plants and “tailing ponds” (deposits of toxic slurry left from processing uranium ore).

Indian and international scientists have long reported that these deformities and diseases are linked to high radiation levels and radioactive debris. Settlements around toxic tailing ponds, they claim, are particularly vulnerable because villagers inevitably come into contact with these waters. Villagers use poisonous water of the river Subarnarekha without being aware of the consequences. However, UCIL says on its website that “the diseases … are not due to radiation but attributed to malnutrition, malaria and unhygienic living conditions [in the villages], and so on”.

UCIL has seven mines in East Singhbhum including Jaduguda. The issue of lethal effects of radiation has come up in court cases, including public interest litigation (PIL) in the Supreme Court (SC) of India. In 2004, a three-judge SC bench dismissed the PIL, reportedly relying on an affidavit filed by the Atomic Energy Commission, which stated that “adequate steps have been taken to check and control the radiation out of the uranium waste”. People’s movements, in and around Jaduguda, have for long highlighted the heavy price villagers pay for their country’s need for uranium.

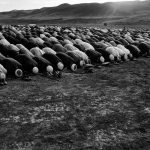

Third Place

© Elliott Verdier, France

This is the story of a former Soviet republic landlocked in central Asia, Kyrgyzstan, home to six million people, esteemed for its nomadic traditions, its yurts, horses, breathtaking mountainous landscapes and steppe … It holds a less perceptible decor, less alluring perhaps, more distant from the stereotypes and necessary embellishments that followed the impenetrable era of the USSR.

How come such photos? These images of desolate landscapes, these troubling portraits of minors, workers, students and elders, these reflections of villages fallen into abeyance, and that sky – that Kyrgyz sky – perpetually seems to give more depth to the many narratives that unfold under its intensity.

These photos are but fragments of reality – facts – in an attempt to reconstitute a concealed story, shattered to pieces, so difficult to gather and put together. With what is left of its broken dreams and surprising vitality, the young republic of Kyrgyzstan is a contradictory Neverland where great aspirations cross paths with remnants of a Soviet era that seem, somehow, frozen in the country’s landscapes and in its people’s minds. A society rooted in environments where pain and isolation come into contact with a somewhat silent resignation.

These images not only show the echoes of a wounded past, but of one that is forgotten, that lurks under the surface, ready to rear its head if paid more attention.

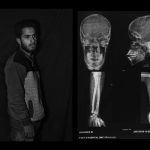

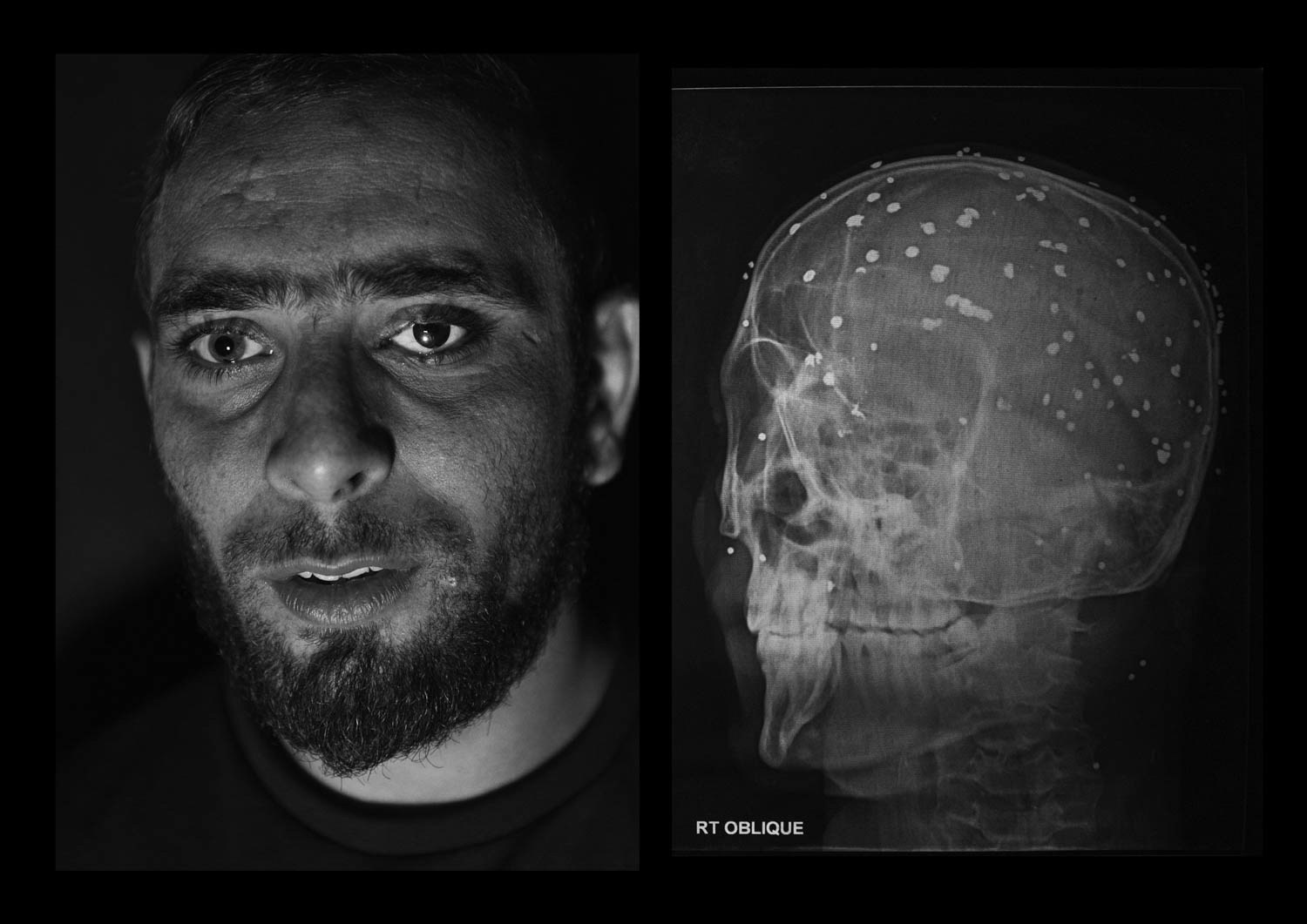

Honourable Mention

© Camillo Pasquarelli, Italy

The valley of Kashmir, a territory disputed by India and Pakistan since 1947, is one of the most militarized zones in the world. In 2010, the Indian government provided the security forces a new weapon which was deployed in the state of Jammu and Kashmir. The weapon is shotgun shells filled with hundreds of small lead pellets which since then have been used to keep urban protests under control. Defined as a “non-lethal” weapon, pellet guns should be aimed at the lower part of the body.

On July 8, 2016, guerrilla group Hizbul-e-Mujahideen’s young commander Burhan Wani was killed in an encounter with the Indian army. Popular, especially among the youth thanks to his use of social networks to spread his message, Wani’s martyrdom was the spark that ignited the entire valley. The government imposed a four-month-long curfew on the local population, while separatist leaders called for continuous strikes.

Hundreds of young boys filled the streets of Kashmir protesting against the “Indian occupation”, throwing stones against the army and the Kashmiri police. Since July 2016, security forces have responded with pellet guns extensively. According to Amnesty International, the new weapon is responsible for blinding hundreds and killing 14 people. Many of the victims were not involved in the clashes with security forces. Those who were hit during the protests tend to avoid speaking about it openly, fearing retaliation by the police.

For youngsters left with one eye, reading has become too painful, forcing them to abandon their studies and giving up the chance of pursuing higher education. Men are left blind and the only breadwinner in families are unable to work and provide for their beloved ones. Carrying dozens of pellets in their bodies, victims face unknown long-term health consequences.

Left partially or totally blind, victims speak of the darkness descended upon their lives. The only things left to see are the faint shadows that surround them.

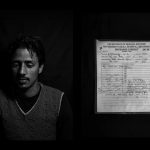

Honourable Mention

© Farshid Tighehsaz, Iran

In 2013, upon developing a skill in social documentary photography, Farshid decided to begin a long-term independent related series which hopes to offer a clearer image of his society (Iran) and is still in progress.

“From Labyrinth” is a multiplicity both in its structure and in its confrontation with the subjects and is about the fears and the effects of the Islamic revolution in Iran as well as the impact of eight years of war that will be felt for generations to come.

Iran had a huge population boom in the 1980s and 1990s, a new generation after revolution and war. It is a generation which played no part in earlier events, and yet what took place affects their lives directly. As the regime’s Islamic doctrine sealed off the country from western influence, the result was a complex mix of contradictions, which fuelled social and political instability.

“‘From Labyrinth’ is coexistence for me as a young Iranian, the generation after revolution, and comment on war with our society and the world”.

Farshid was born on July 21, 1987 in Tabriz, Iran. His birth year coincided with the last year of the Iran–Iraq War. Being young in Iran meant limitations: limitations in which religion affects politics, art, culture, diversion, economy, education, clothing, speech, behaviour, femininity, masculinity, relationships and life. The impact of these events on our lives and souls will always be visible. In this personal project, Farshid is searching for evidence of the growing complexity and depression both in sociological and psychological terms.

“Some commonalities among my peers were discovered: fear – fear of the future; fear of annihilation, fear of sexuality, fear of loneliness and the fear of not being happy”.

These fears take control of each individual’s life and identity, in ways both unique to every person and universal.

Next:

Booooooom x Capture Photography Festival: Public Art Open Call

Share: