Boutographies European Festival of Contemporary Creative Photography

© Camille Gharbi, France, lives and works in Paris

Living spaces

Edition 2018

© Camille Gharbi, France, lives and works in Paris

Edition 2018

These images were made in the spring of 2016, in what was called the Calais Jungle. They show some of the constructions existing at the time in the Lande camp, which housed several thousand asylum seekers, and which was demolished on the orders of the Interior Ministry in the autumn of 2016.

The constructions shown here are decontextualised. They are isolated from their environment, which has focalised the media for so many years; upon which so much has been written, read, shown, observed, and finally, for want of better, destroyed. Perhaps in order to no longer see it.

These constructions appear here, in front of us, removed from the pandemonium of daily life. They no longer tell of an inextricable situation, they are no longer the symbol of a world crisis or a predicament that we don’t know how to resolve. They are simply here, and speak only for themselves. They attract our attention. Violently sometimes, but with humour also. Over and above the clichés, the desolate representations, the prejudices that we associate with this particular world that is the Calais Jungle, they demonstrate the formidable resilience shown by those who built them. They speak of lives in the process of reconstruction, of ingenuity, hope, mutual help, cooperation, suffering and optimism.

They speak to us, quite simply, of the desire to live, and the force that can come from that. Something that, in another context, we would have perhaps more readily seen.

NB: In February 2016, the Administrative Tribunal of Lille validated the principal of the evacuation of the southern part of the Jungle. However, the judge noted the installation of “living spaces”, created by the migrants, “which are necessary, and to which they are attached, in particular for cultural reasons” Consequently the judge decided that the evacuation order should not include these “living spaces”.

In consideration of this judgement, migrants and welfare associations wrote on a large number of cabins, shacks and other constructions housing refugees, the words “living space”.

© Carlo Lombardi, Italy, Lives and works in Pescara (Italy)

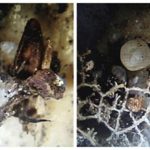

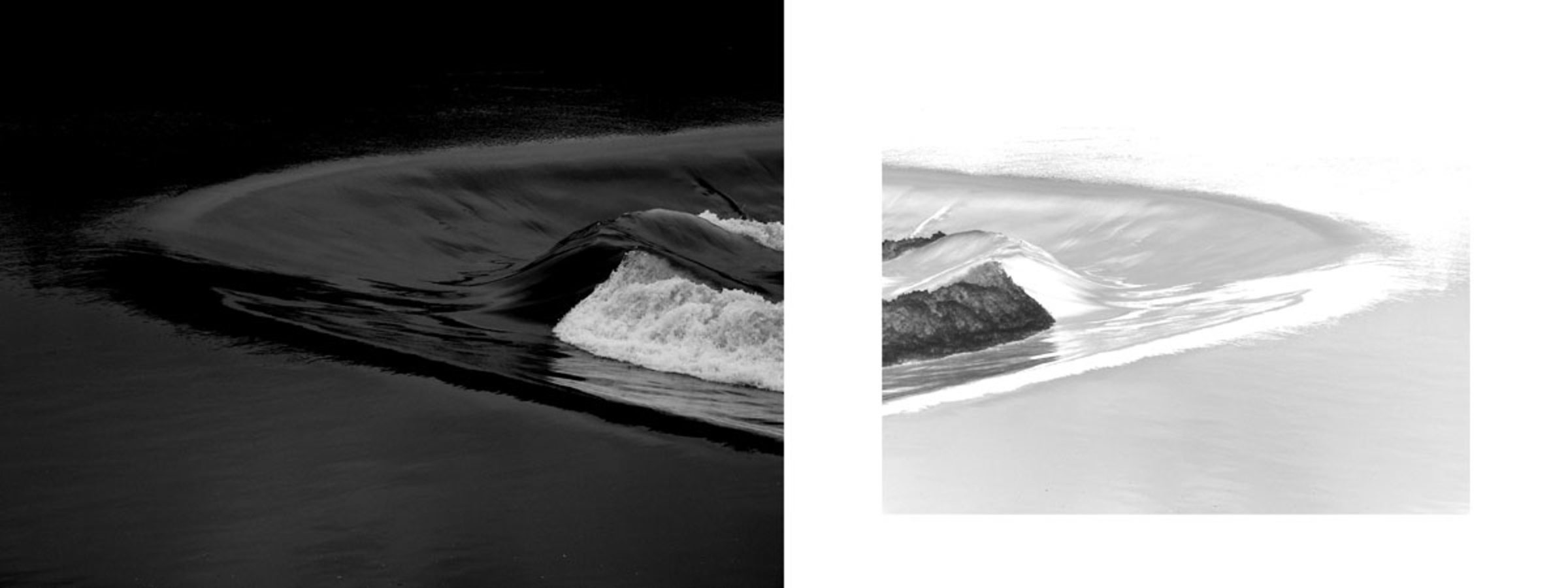

Dead Sea

Edition 2018

© Carlo Lombardi, Italy, Lives and works in Pescara (Italy)

Edition 2018

The loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) lives in oceans and seas all over the world, but prefers breeding in temperate and subtropical regions. Since 2015, Caretta caretta has been included on the Red List of the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) as a vulnerable species, subject to extinction. Scientists believe that the world population of this species is decreasing.

These animals are very fragile and suffer from the consequences of various human activities. The exploitation of the coastlines, which generates artificial light perturbing the breeding areas, global warming (the increase of the sand temperature inside the nests affects the sex of the embryos), pollution and accidental capture are the main threats to this species.

The under population is especially notable in the eastern part of the Mediterranean area, while few nests are recorded in the western part. Each year, about 150,000 turtles are accidentally captured. They are principally victims of indiscriminate fishing, with nets and baits, static lines, trawls and bottom gill nets. For their part, 40,000 deaths can be attributed to deliberate fishing or to collisions with boats or the ingestion of plastic material.

Even if man, in these circumstances, appears as a persecutor, he also disposes of all the means to put an end to this massacre. Networks of professionals (doctors, vets, biologists, marine biologists) voluntarily and constantly carry out various research activities, surveys and awareness campaigns. Each year, thanks to their involvement and collaborative work, hundreds of specimens are saved and released back into their natural sea habitat.

© Cédric Calandraud, France, lives and works in Paris

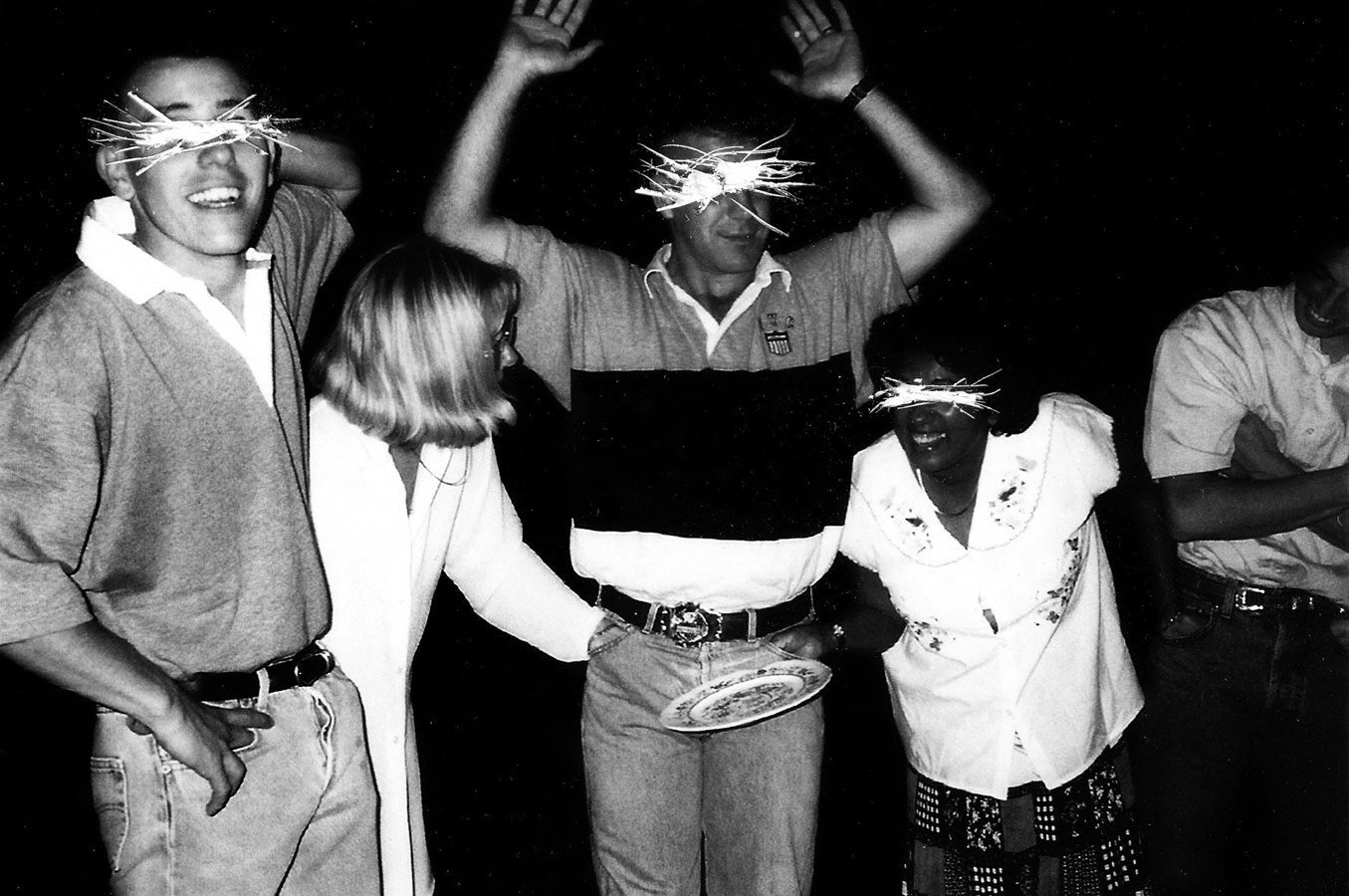

France 98

Edition 2018

© Cédric Calandraud, France, lives and works in Paris

Edition 2018

I took these photos during my adolescence, between 10 and 17 years old, in the village of Yvrac, in the south west of France, where I grew up. At that time I took lots of photos with a disposable camera of the numerous family reunions where there was always something to celebrate – a christening, a birthday, a wedding, etc.

These moments of festivity were, naturally, only one aspect of our lives: a distraction after a week of work. You never photographed the worst moments. It’s that in fact that struck me on rediscovering these images piled in a corner of my teenage bedroom. A number of people shown in these photos were struck down by illness or alcoholism, amongst them my father, who died during this period. Others lost their houses, their family or their jobs. These are the images that are the most powerful in my mind, but which are completely absent from the photos themselves.

In order to rediscover the forgotten part of my family history, I decided to reclaim them. Since the negatives had not been kept, I worked directly on the prints, often already damaged. By effacing the eyes, by isolating the details or the bodies, or by masking parts out, I hope to give new life to these images, isolated from their time and their reality, in the hope that those forgotten moments resurface around these photos.

The title of this series is a reference to a symbolic date, that of the summer of ’98, which was a milestone in my life as a child. I was barely seven years old, but I remember that summer as one of my first experiences – the experience of happiness, of love and of death.

© Dieter De Lathauwer, Belgium, lives and works in Ghent

I loved my wife

Edition 2018

© Dieter De Lathauwer, Belgium, lives and works in Ghent

Edition 2018

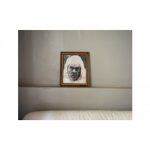

This exhibition questions the value of a person when compared to their level of utility or cost to society, and investigates the manipulative power of propaganda images. The exhibition treats the elimination of incurable physical and mentally ill patients, both children and adults, between 1939 and 1941. The killings were framed as “mercy killing” and “euthanasia” and served as a precursor for the Holocaust. In a structured and organized way over 70.000 patients were murdered in Austria. They were considered as useless to society, and so should present no financial burden on that society. In 1941 Hitler ordered the program to stop, but the institutions continued despite that. Only a few of the responsible persons were ever brought to justice.

I travelled through Austria photographing these care centres and psychiatric institutions, and I combined these in situ photographs with stills from Nazi propaganda movies on euthanasia, digital collages and photographs of historical objects. The digital collages represent some of those responsible for the assassinations, in which some facial features have been replaced by Google images of the ideal face, of perfect features, thus recalling Nazi eugenics.

The images can be read in different ways. Even though all the photographs are true, multiple interpretations and directions are possible.

The design of the book has references to a medical file. It is packed in a pink two-pocket folder containing also a small booklet with three essays and a map. Every folder has a manually signed red cross on the cover just like the doctors did when judging someone to be incurable hence to be eliminated. The small booklet is printed on thin paper and small font size just like a medical leaflet.

The title is from a dialogue in a propaganda film where the person accused of committing euthanasia on his wife is brought to court. He stood up and said “I loved my wife” yet at the same time the underlying theme of the movie is “even though I loved my wife, killing her was the only right thing to do for the sake of the national interest”. This episode could be seen both as a family drama and an apology for Nazi eugenics.

This project brings together several of my interests in photography: the exploration of places through social and historical blind spots, how people understand the photographs within their environment, and the photobook as an object in its own right.

© Florence Iff, Switzerland, lives and works in Zurich

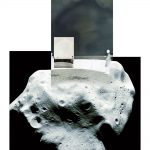

67P

Edition 2018

© Florence Iff, Switzerland, lives and works in Zurich

Edition 2018

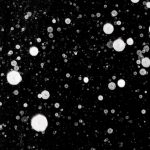

This project is an investigation of light, time and space on the one hand within the subject of photography itself and on the other hand of the example of the space mission „Rosetta“. Images from NASA and ESA depict the journey to the comet 67P, the destination of the mission „Rosetta“ in the search for the primeval soup and the proof of life-bearing molecules within the universe. The whole mission started 1992 and lasted till 2014, when the lander finally touched down on 67P to gather information. This high-tech mission was developed to answer questions about life on earth.

Old deteriorating, fading or double-exposed (glass) negatives illustrate the subject of ephemerality and impermanence.

Pictures of the human body, such as skin, CTI’s or X-rays are included in order to stress the fact that our existence consists essentially of being organic. Old photographs of long changed landscapes merge or coexist with high-tech images of Mars or the surface of 67P.

Playing with these juxtapositions I created a visual journey approaching universal questions on life, transiency, time, what remains from our existence and which imprints we leave behind as human beings.

Simultaneously it’s a journey through 100 years of technical advancement within photography and space-exploration.

The pictures are named after the 11 scientific instruments and the lander on board “Rosetta”.

© Hanna Rast, Finland, lives and works in Helsinki

Pine Needles

Edition 2018

© Hanna Rast, Finland, lives and works in Helsinki

Edition 2018

There is no tangible time in the growth of a person; there are only transitions. By this I mean how we change in our bodies, minds and consciousness when becoming adults. Meanwhile, we are very sensitive to shifts and distractions from the outside world. These distractions may remarkably affect how we perceive the world and ourselves.

My series Pine needles examines the role of photography in representing identity and the distractions and interruptions that may push us off the path of normal development. Sudden turns of events can change our perception of trust, personality and self- confidence. My works are based on personal experiences and by connecting these with my artistic work, I am trying to define how our personalities might suddenly change and how understanding the past is necessary for the present self.

I apply old photographs with new ones to reconstruct an image of my own identity. The method is simultaneously a sort of a study on how to take control over one’s own narrative. While working with the images, I am no longer an observer – I am becoming a participant. In this process, the most important part is to engage oneself on the level of comprehension. Photographs may show us our past, but what we do with them and how we use them is about today, not yesterday. The traces of our former lives are utilized in a never-ending process of making, remaking and making sense of ourselves today.

© Karim El Maktafi, Italy Morocco, Lives and works in Padenghe sul Garda (Brescia)

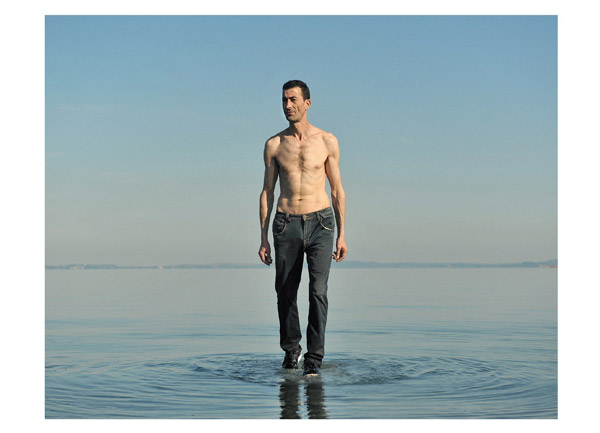

Hayati

Edition 2018

© Karim El Maktafi, Italy Morocco, Lives and works in Padenghe sul Garda (Brescia)

Edition 2018

Hayati (“my life” in Arabic) is a visual journal realized exclusively with a smartphone. Hayati reflects on my identity as a second-generation Italian. Son of immigrants, born and raised in Italy, balance between two realities that at first sight might seem incompatible.

To produce this story, I became both its subject and its object. I was born in Desenzano del Garda, a village near Brescia, Italy, from Moroccan parents. Growing up between two worlds forced me to sharpen my gaze and to compare points of view which often diverge from each other. Embracing a single identity is not easy; feeling out of place or like an odd cultural hybrid often happens. Yet, while trying to define this identity, one understands the privilege of “standing on a doorstep” on the edge of two environments.

One can decide who to be, where to belong, or to create new ties, while keeping alive the experiences learnt along the path. One must learn to juggle multiple languages, cultural taboos, references, prohibitions, and learn to make yourself understood to those who are not themselves standing between two worlds.

I had to travel inside my own life and family. I faced doubts, hesitations and afterthoughts, but I produced an honest portrait of how I have lived until today. The most interesting aspect of this story — of my story — is the creation of a less restricted reality. One that is undefined, in which various beliefs and experiences thrive and form a unique harmony.

Hayati was realized between Italy and Morocco during a year-long scholarship at Fabrica, Benetton Group’s communication research centre based in Treviso, Italy.

© Lee-Marie Sadek, France, lives and work in Créteil (France)

I Kiss Holes for the Bullets

Edition 2018

© Lee-Marie Sadek, France, lives and work in Créteil (France)

Edition 2018

The following images show my states of depression, melancholy, anxiety, insomnia, paranoia, isolation, loneliness, emptiness and weariness. It is an invading and never-ending bipolar disorder through which I never cease to question myself: why am I so detached from reality? So disappointed by it? Never being able to cope with it?

“Clarity is not born of what we imagine to be clear, but of our awareness of the obscurity.” Carl Gustav Jung.

The first part of the title is a lyric from a song called “Rosary” by Scott Walker.

© Manon Lanjouère, France, lives and works in Paris

Bleu Glacé -Lexique des paysages islandais-

Edition 2018

© Manon Lanjouère, France, lives and works in Paris

Edition 2018

Bleu Glacé is a cabinet of curiosities, a « scientific » study which synthetically reconstructs the Icelandic landscape.

If Iceland attracts so much attention, it is often because of its geological particularities. « Its landscapes are a formidable geology lesson, a mail-order catalogue of glacial and volcanic forms » writes Michel Tournier in his novel Les Météores. Bleu Glacé is a sort of catalogue of landscapes that an immobile or armchair traveller might imagine to find in Iceland.

The imagination forms the object that we are thinking of and that we desire, directly, in front of our eyes so we may take possession of it. The image thus created is a mental one, recreated in a studio. The object itself is absent, but all its qualities are there; the impression is present, as are the persons which, although they resemble human beings, are just persons, without intent.

Within the objects I create, one is free to see a waterfall, an iceberg, a plastic sheet or a block of polystyrene. The imitation is only partial, since only certain elements are reproduced. The images thus created seek to invoke this « primal ardour of water, wind, clouds, of colours projected in their purest states on the skies and horizons » that Samivel describes in his book L’Or de l’Islande.

Bleu Glacé hopes to represent this mythical elsewhere, a land still unknown.

© Patrick Wack, French, Lives and works in China

Our West

Edition 2018

© Patrick Wack, French, Lives and works in China

Edition 2018

Borrowing from romanticized notions of the American frontier, synonymous with ideals of exploration and expansion, photographer Patrick Wack captures a visual narrative of China’s westernmost region—Xinjiang. Whereas the American West conjures images of cowboys and pioneers, of manifest destiny and individualistic freedom, the Chinese West has not yet been so defined. It is a place of pluralities—of haunting, expansive landscapes, of rough mountains and vivid lakes, of new construction and oil fields, of abandoned structures in decaying towns, of devout faith and calls to prayer, of silence and maligned minorities, of opportunity and uncertain futures. It is a land of shifting identity. In essence, Xinjiang is the new frontier to be conquered and pondered.

Literally translating as “new frontier” in Chinese, Xinjiang is a land apart, and has been so for centuries. More than twice the land area of France with a population less than the city of Shanghai, the Chinese province of Xinjiang once connected China to Central Asia and Europe as the first leg of the ancient Silk Road. Yet it remains physically, culturally, and politically distinct, an otherness within modern China. Its infinite sense of space; its flowing Arabic scripts and mosque-filled cityscapes; its designation as an autonomous region; and simmering beneath, its uneasy relationship with the encroaching, imposing, surveying East. For China’s ethnic Han majority, Xinjiang is once again the new frontier, to be awakened for Beijing’s new Silk Road—China’s own manifest destiny—with the promise of prosperity in its plentiful oil fields. For Patrick Wack, Out West is as a much a story of the region as it is his own, as much a documentation of a contemporary and historical place as it is an emotional journey of what it means to strive, and for what. There exists an inherent fascination in the region—as both key and foil to the new China—and a siren’s call to its vast limitlessness that instinctively incites introspection and desire. Showcasing a romanticism of the frontier, Out West presents Xinjiang via the lens of its present day, in photography that speaks of the surrealistic tranquillity—and disquiet—of the unknown.

Out West offers an experience of Xinjiang that highlights its estrangement from contemporary perceptions of the new China, accentuating undercurrents of tension and the mystique it has cultivated—whether in their minds or ours. At its core, Out West is a question of perspective: What is the West but the East to another?

© Philippe Leroux, France, lives and works in Marseille

Brassage

Edition 2018

© Philippe Leroux, France, lives and works in Marseille

Edition 2018

They arrived by the sea. Slimane, Artak, Alain, Hayarpi, Hasmik walk on water. Their silhouettes stand out against the azure horizon. Their faces are serious. A far away look in their eyes. Fatigue counts for little against their determination. Before, they crossed mountains, traversed cities, abandoned parents and friends, left the family home. Leave in order to work, pay to find refuge, pay to avoid dying; go into exile to escape ostracism, war, misery. Leave to save the children. They dreamed of asylum, they are still dreaming of it. Who can give up the dream of asylum?

And afterwards? Shadows. How can you build a home when everything leads you towards a state of invisibility, of un-detectability; when everything obliges you to melt into the exploited and indistinct mass of exiles, the asylum seekers, the refugees? The singularities, the multiplicity of histories matter little since, finally, they are all baptised with a new name: Migrants. That is their new semblance. That is the new moral doctrine: conform or disappear from the sight of others. That is their outlook.

But here is what we can also read in this panorama: the sculpting of footprints and itineraries, the material of time immemorial; treads solidified in the grey clay, waste heaps of feet and soles which frolic and intermingle with the prints of the grey heron, kingfisher and teal; fluttering of birds, little dances on the sea, a dress in the water, a young girl dancing, shells in her hands, faces in the sand, the tears of a jellyfish: brassage (fusion?)

© Sandrine Elberg, France

Yuki-Onna

Edition 2018

© Sandrine Elberg, France

Edition 2018

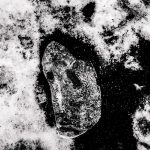

Sandrine Elberg’s photographic work mixes a quest for personal identity with more formal exploration. Here, wearing the mask of Shakumi, a young girl from the Nô theatre, she takes on the persona of Yuki-Onna, inviting us to indulge in fantasy and contemplation. Yuki-Onna is a character from Japanese folklore: the Snow Woman. She is a Yokaï, a spirit or phantom which appears at night in the regions of heavy snowfall. She is described in various ways, sometimes as an immense figure, sometimes as the incarnation of a snowy landscape. She is the personification of winter, in particular the snowstorms. Yuki-Onna represents the duality of winter: from her smooth, cold beauty is born the cruelty of tempests.

Sandrine Elberg intermingles digital photography with photograms and chimigrams. An important part of her work is realised on the printed image itself.

Boutographies European Festival of Contemporary Creative Photography

Share: